Condos in Chicago

A deep dive into the history, economics of condo construction and what we are and aren't building in the City of Chicago

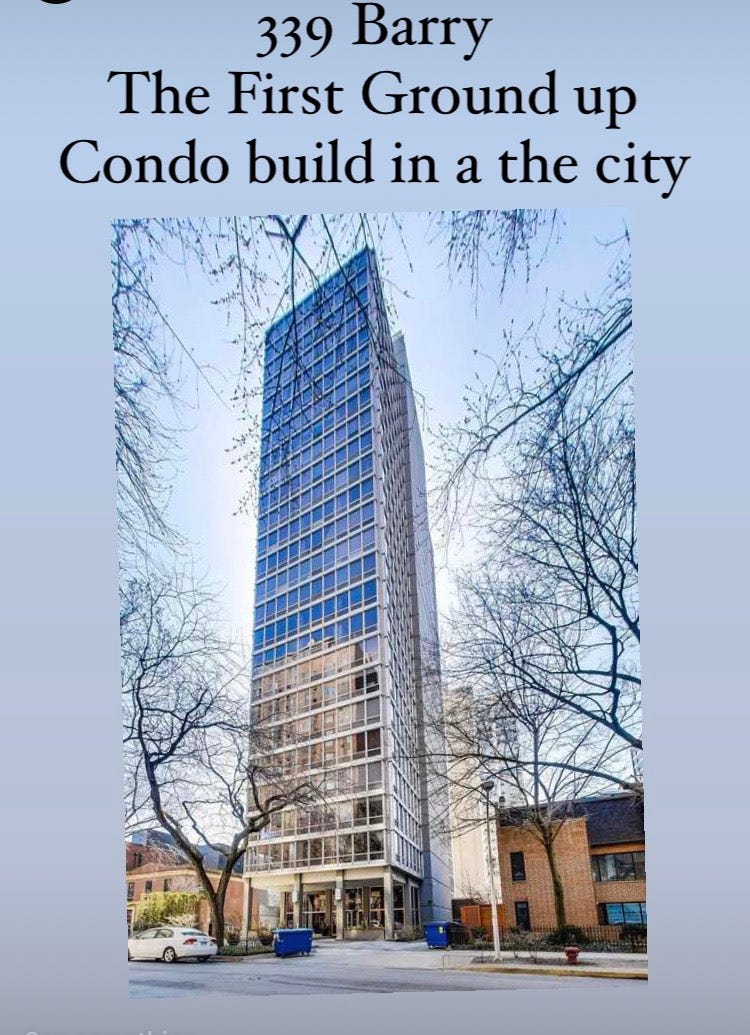

The Illinois Condominium Property Act was passed in 1963 and with it came a whole new way to look at urban housing. Residents who rented for years or sometimes decades could now own their apartments as a single piece of property for the same or sometimes less than what they paid in rent every month. Cities liked condos too. Multiple pieces of property within one building resulted in a higher tax yield than a single 1 PIN building. This first condo wave saw new build projects like the corridor of high rises on North Sheridan or Lake Shore Drive, as well as recently completed large scale rental projects like Marina City and Sandburg Village, go condo within about a decade of their construction.

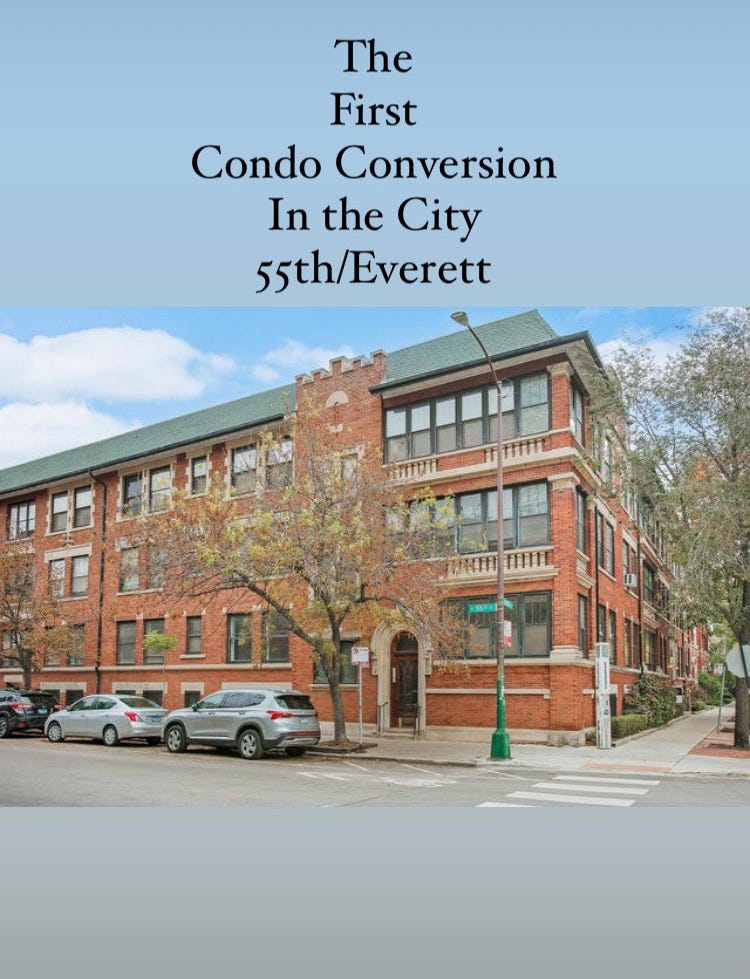

As this first wave of “condomania” grew, the next step after posh midcentury high rises was the conversion of the privately owned, turn of the century low rise apartment buildings. Long time landlords were happy to ditch stagnating rents and growing overhead like taxes and energy costs eating into their rental profits, and the prospect of selling each unit rather than the whole building for a higher net return was sounding pretty great. This trend started to kick off in the early to mid-70s in neighborhoods like Lakeview, Lincoln Park, Edgewater, Hyde Park, Kenwood and Uptown. Back then, it was common practice for these smaller landlords to just sell the unit without rehabbing it to the tenant, and if the tenant wasn’t interested (even under pressure, which was commonplace), they’d exercise the very lax pre-1978 tenant kick out rules to find a buyer.

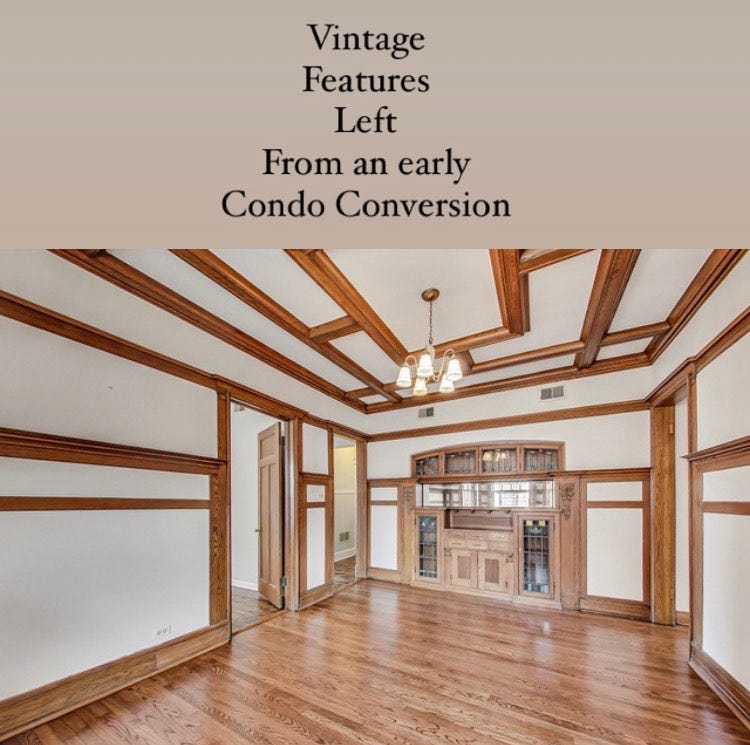

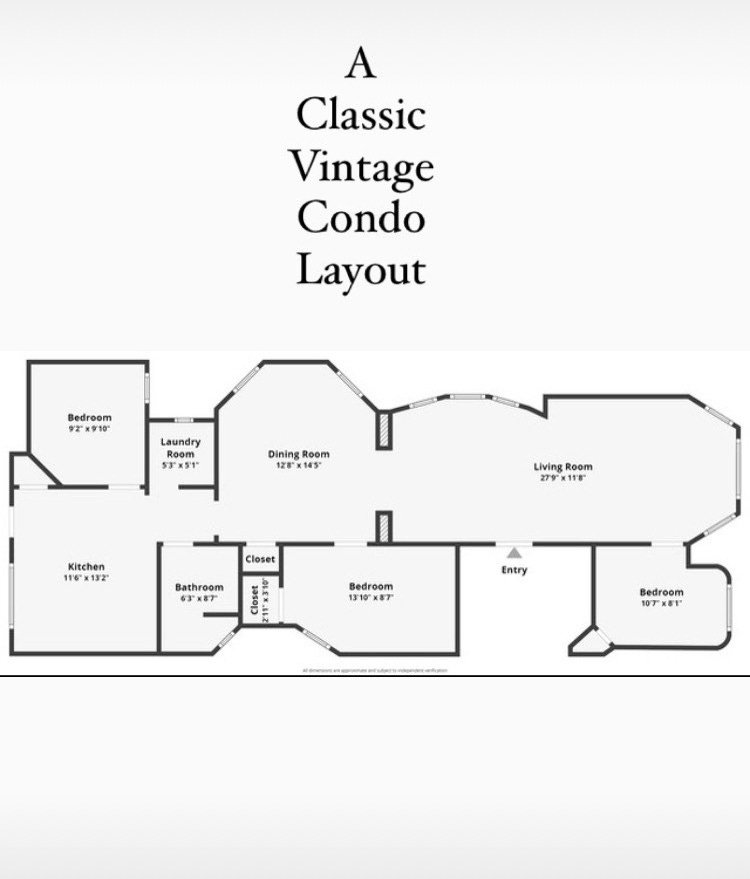

The reason so many of the condos in these areas look how they did both internally and externally when they were originally built as apartments over 100 years ago is economic over aesthetic. Small landlords wanted to have to do as little work as possible to maximize their profits. After the building goes condo and after the articles of incorporation are issued and the control is shifted from the landlord to the HOA, changing a unit’s layout and moving common plumbing and electric around to accommodate a single unit’s needs is extremely difficult to orchestrate. This level of construction in one unit depends on the cooperation of the entire HOA who all have a shared interest in the building’s utilities.

In other words, if you bought a 1bath condo, chances are you’re stuck with it. Don’t count on the HOA letting you move common plumbing around.

Abuses by landlords and builders in early condo conversions drew eyes and lots of media attention in the late 1970s. This led to several amendments to the 1963 ICPA act. These extra compliance hoops meant that what was once relatively easy process of landlord selling direct to tenant/buyer turned into landlords taking the easy buy from developers who dealt with the compliance hoops and tenant move outs and then did the conversion and sell out themselves.

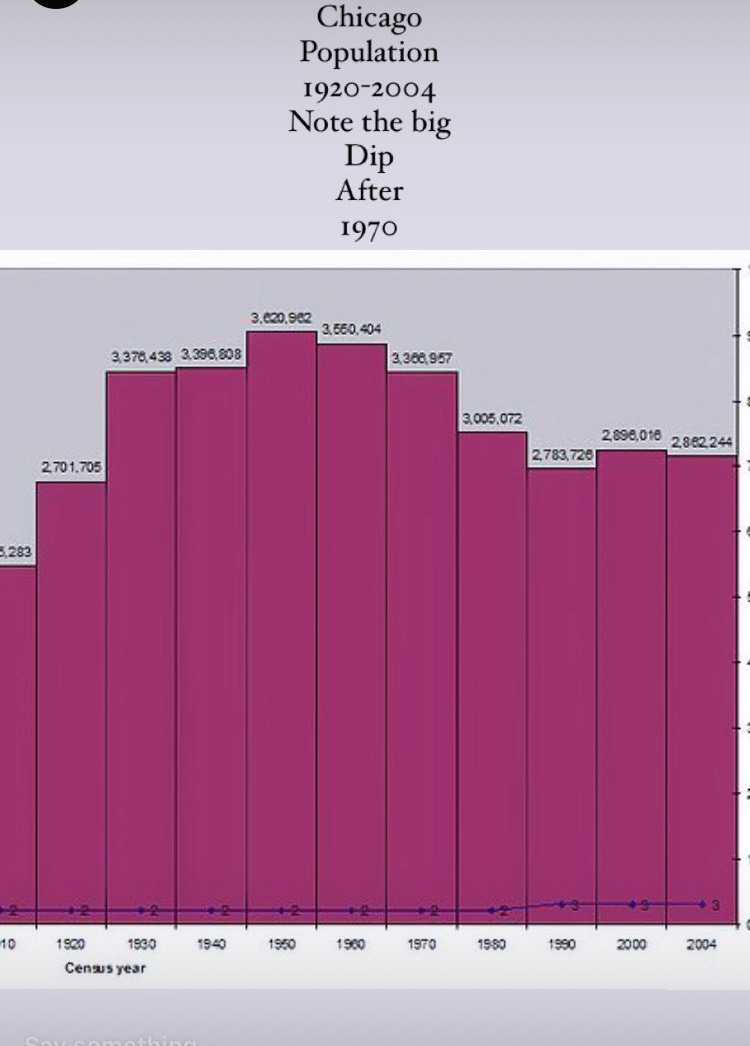

Around the same time, turbulent inflation caused the Fed to raise interest rates, pushing the average mortgage rate to the high teens and causing a recession, pumping the brakes on condomania and the housing market in general. In addition, the 1980s saw a new wave of suburban sprawl by the first generation of baby boomers leaving city life, starting families, and buying single family homes. In this decade, Chicago saw its biggest net population loss (10.7%) since its incorporation, further damaging the city condo market in the following years.

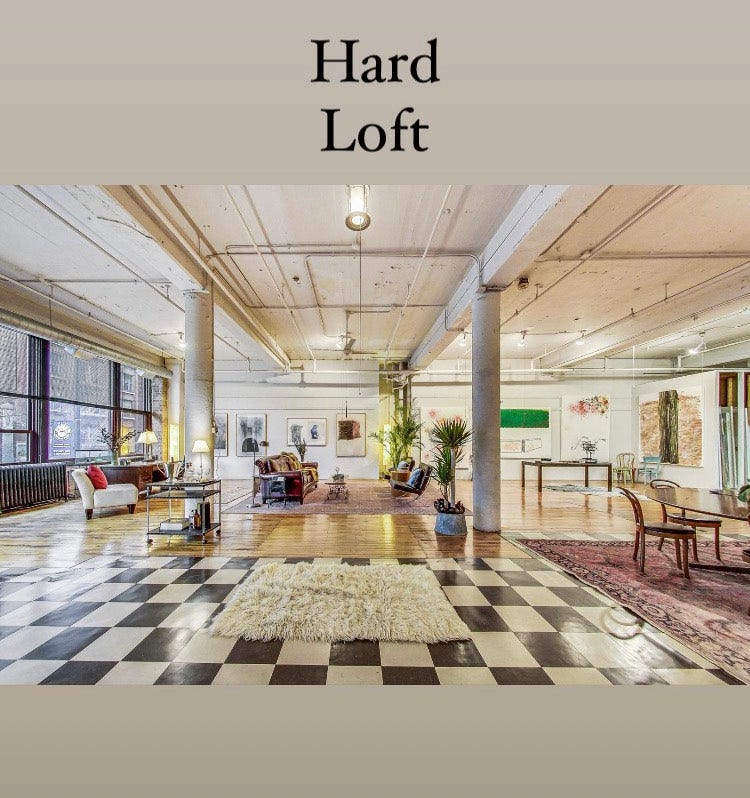

In the late 80s and early 90s, a new generation of upwardly mobile urbanites began to move into the city en masse. This coincided with the American economy at large moving away from heavy manufacturing leaving massive vacant industrial buildings in core urban neighborhoods. At the same time, the lore of the downtown New York artist type and their takeover of these massive raw loft spaces had grown to epic proportions. The loft conversion eventually began to become the vanguard housing model of the new yuppie urban living takeover of the 1990s. These long suffering 100 year old industrial buildings in River North, South and West Loop, West Lincoln Park and Bucktown were converted by developers at first to huge and raw to eventually to tiny “soft” lofts ushering into the mainstream open concept with all the living and kitchen space in the open and on display, a look that remains prevalent in condos today.

The early 2000s saw a tremendous rise of subprime loans. Purchases originally financed by FHA conforming condo loans in the 60s and 70s eventually gave way to more subprime products, which with their ridiculously lax borrower qualifications and deliberately confusing interest structures significantly broadened the base of prospective home buyers and those looking for cheap money for investments. Demand for more and more of these mortgages to securitize from investment banks pushed rate structures and qualification standards from originators even lower.

2005 saw the biggest year for condo deliveries since the late 1970s with 3,975 units coming to market. Much of this was centered on the then booming ground up River North tower market. But for developers looking for a lighter lift, what housing stock ripe for buyers was left to convert after the 2 previous conversion waves? Along with the conversion of the “B” stock of 70s and 80s downtown high-rises, rumbles of gentrification saw developers take big speculative bets and to look south and west.

Similar to practices in the mid-1970s, turn of the century apartment buildings were in developers’ crosshairs but this time in Logan Square, Humboldt Park, Near West Side, Albany Park, and Bronzeville. What was different this time for conversions? Builders now knew simply parceling off the existing units and selling them like we saw in the 1970s was impossible, so they started thinking: money is cheap, land in these neighborhoods is cheap why not gut the building, give buyers that of the moment “open feel” and fatten the margins more. If the building can’t support these trendy open floor plans just tear it down and build new.

.

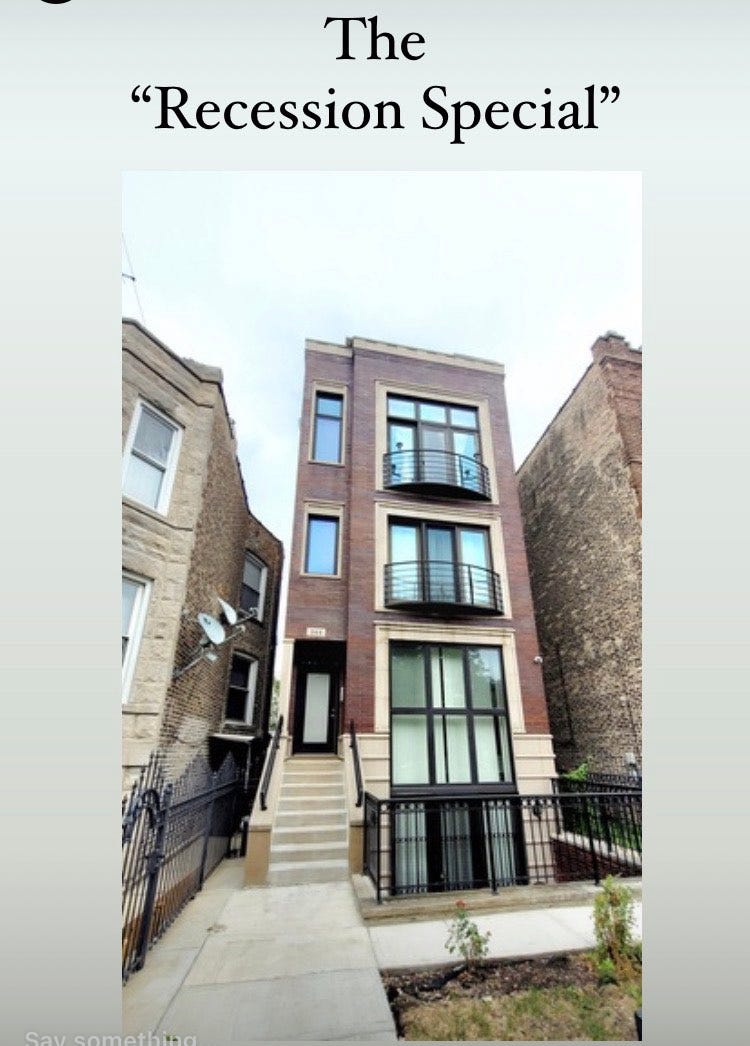

Waves of teardowns also rolled through neighborhoods where land was cheap. These were often in areas adjacent to neighborhoods with an already ”it” status. Think East Humboldt and East Village to Wicker Park, West Lakeview and Bucktown to Lincoln Park etc. Even when there were not sufficient comparable sales for appraisal in these neighborhoods, lending practices at the time were so loose that builders were still confident the buyer could get a loan approval and close.

One of the most visible reminders of the subprime mortgage crisis locally is the sea of these hastily built, remarkably similar condos, many of which were still underwater from their initial sale price until just the last few years. You know which I mean: The brown cabinets, the Brazilian cherry floors, weirdly placed exposed brick, huge bedroom in the back and the kitchen plopped in the center of the living room. Many in real estate communities call them “The Recession Special” and if you had one of these listings in the 2010s you knew how difficult they could be to sell.

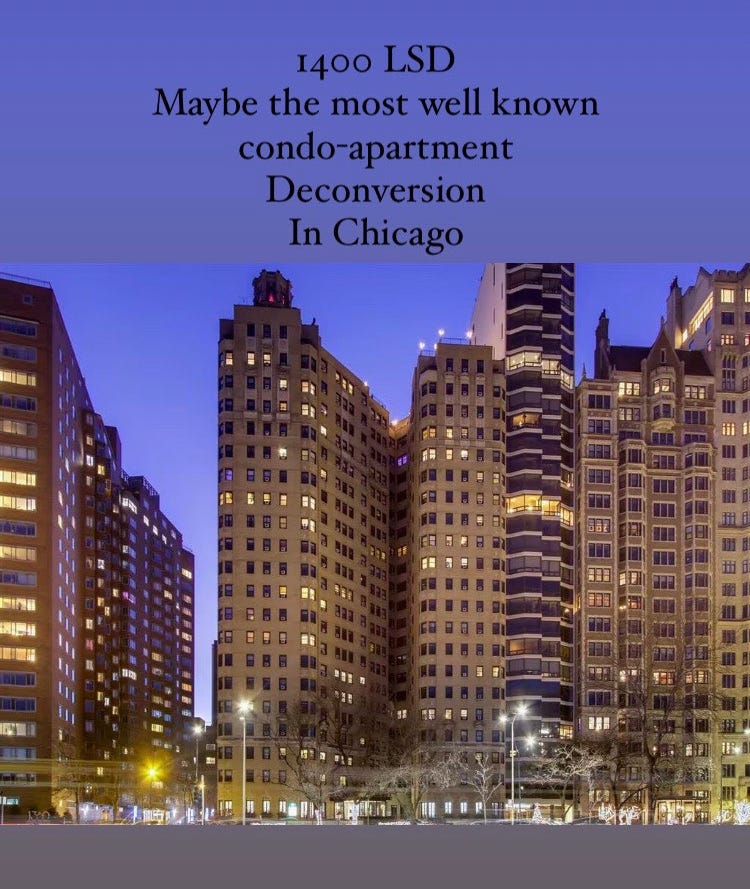

No condos languished on the market post ’08 quite like the original apartment-to-condo-conversions in Streeterville, Gold Coast, Old Town. In the last 15 years, demand has been so low in some of these buildings that many HOAs found selling the buildings in their entirety to investors who would then DE-convert them back to apartments was a better chance to get out from under their pre-recession buy price. After a big wave of these projects in the 2010s, changes to recent laws have upped the owner voting percentage minimum from 75 to 85% for a deconversion to pass. This, along with massive changes in debt accessibility has stemmed growth of the deconversion market especially in large downtown buildings

.

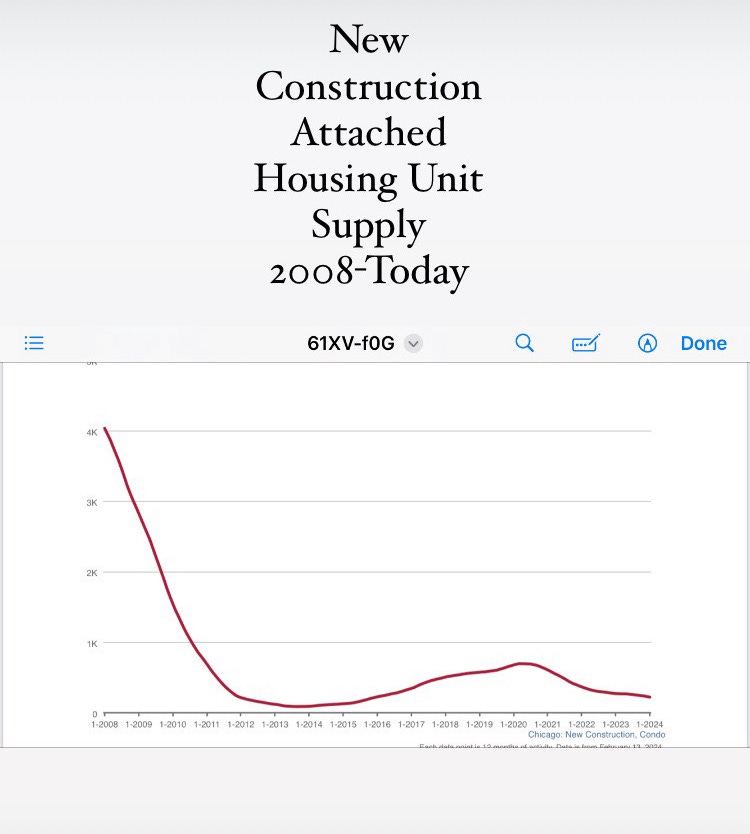

The Covid buyer frenzy has been the latest shake up in the condo market. Over the last 2 years, condo demand is the strongest it’s been since 2006. Low rates have been the main driver but soaring single family home prices, abysmal existing inventory on market, and a return from covid exoduses to urban life all seem to be at play. Still, very little new condo stock is being added each year. In the entire City of Chicago, there are currently only 233 new construction condos on the market, in January 2008 there were 4,033.

Today we see cranes everywhere, new permits on old buildings, whole neighborhoods being created. Next to NONE of these are for sale. What are we building now, what aren’t we building now and why you might never see a new construction condo outside of the luxury market again.

_________________________________________________________________________

Part Two: Cranes Don’t Equal Condos?

Has anyone ever pointed out a new glassy high rise, or a gutted out old building in Chicago to you and said something like “Oh yeah, ‘they’ are putting new condos here.” I think the 2000s condo boom etched the idea into people’s heads that large scale development must equal homeownership. In reality, next to none of these high profile developments you’ve seen popping up over the city in the last decade have been condos. Why would developers throw so much weight behind rental housing in a country where 66% of the population are homeowners?

Pre/Post Recession Building Shift:

After the disastrous value destruction in the real estate market post 2008, investors began to take note when rents(and eventually values) in Multi Family Assets began to swing back faster than those in other sectors of commercial real estate. Why? Wealth destruction, a contracting economy saw more rental occupancy and for longer periods. In 2008 the average first time homebuyer was 30 years old. Today they are 35.

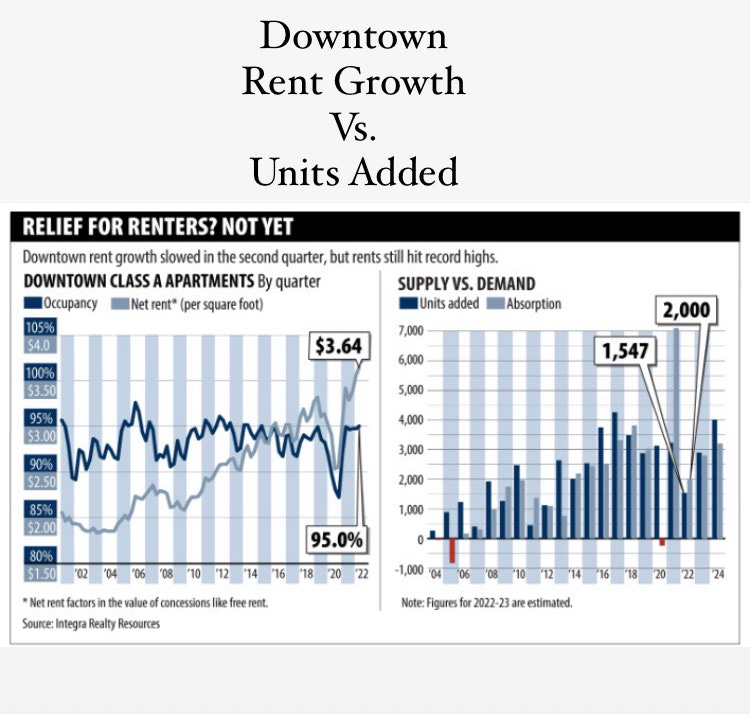

It didn’t take long for investors to notice this trend. Nor did it take them long to notice to continued trend of young professional migration to Chicago’s city center without new product to meet the demand. In the years prior to 2008 rental units added annually in Chicago rarely surpassed several hundred units. By the time the mid 2010s rolled around Chicago was adding over 3000 rental units annually.

It wasn’t just large scale institutional money noticing this trend of rent prices increasing amidst diminished buying power. Small scale landlords were getting into the market too. 2-4 Unit prices in Chicago have jumped 260% since 1/2014 with a 26% jump between 2020-2022 alone. Low interest rates and the trend of “house hacking” online content fueled this boom in many first time home buyers locally opting to buy multi unit buildings over condos.

In the midst of the last condo boom, for every glassy, luxury amenity filled high rise unit, there existed an affordable counterpart in an old retrofitted Chicago apartment building. While first time buyer demand for these downtown units have been stifled by high HOAs, transient attractions to downtown and diminished cultural relevancy, the existing condo market in the neighborhood turn of the century walkups is still soaring. So why aren’t we building more of them?

1:

The idea of protracted home ownership timelines fueled by data on millennial and Gen Z household wealth vs Gen X and Boomers at the same ages still keeps builders’ confidences in Multi Family projects over condo conversions for mid priced existing buildings. Higher rent prices in these buildings means higher property valuations which make buying an expensive multi family building untenable for a profitable condo sell out when factoring in the construction costs to bring units to market.

2:

Condo conversions are not what they once were. Even if building codes hadn’t changed since the 70s, buyers are just too savvy now to buy into an old apartment building where the mechanicals, windows, roof, brick haven’t been touched by the developer as was the former practice. The standardization of home inspections in transactions, more rigorous building codes and insurance standards have made these simple conversions to condo from beat up vintage buildings all but impossible today.

So what are we building and where?

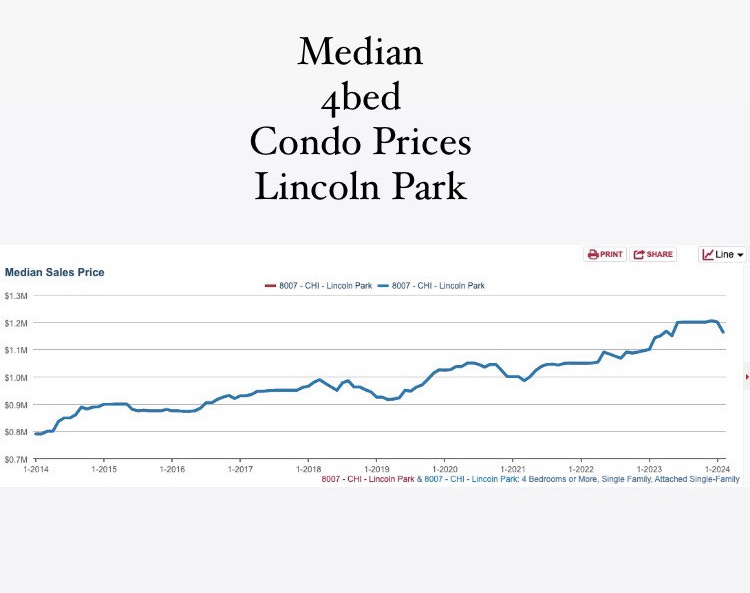

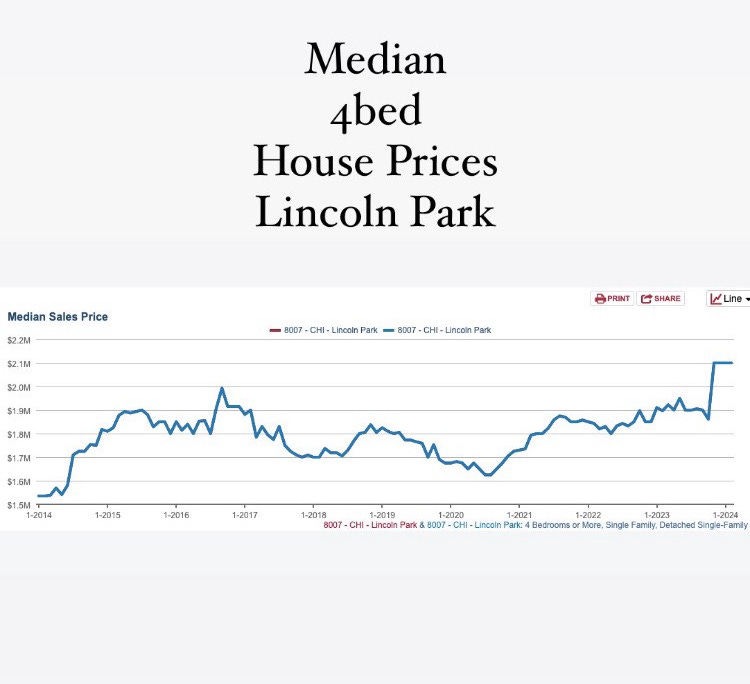

Developers these days are most confident in the luxury market for large condos that can act as single family home alternatives in tried and true upper middle class neighborhoods. With enormous price growth and demand for single family homes at an all time high in these neighborhoods, a sub market for larger scale condos has emerged.

The thought behind this is even at historically high prices these 3-4 bedroom multi level condos are still priced at market between 40-60% of the cost of a single family home with a comparable level of finishes in the same areas. With no end in site to the boom in SFH prices, this allows buyers to experience the conveniences of these inner ring neighborhoods and have a large enough space to satisfy multiple living arrangements.

Let’s look at this in practice:

This lovely house in Lincoln Park seemed to be totally suitable for single family occupancy but because of the prime location and wider than average lot it was torn down 16 months ago and replaced with 3 condos. Sold for $1.3m.

The Condos:

The sale price for each condo was:

Top Floor: $1.385m

Middle Floor: $1.099m

First Floor(duplex down) Under Contract with asking of $1.649m

Even if this seems high in price to you. Keep in mind the median sale price of a 4bed house in Lincoln Park is $2.1m. This trend has continued to grow, especially in the dozen or so North Side neighborhoods with high density and exceptional school districts.

____________________________________________________________________________

Part 3: 30,000 Vacant Lots in our “World City.” Urban Renewal, Depopulation and Its Effects on Building Today

Mid Century Land Clearance

What has shaped up to be one of Chicago’s most shameful legacies was a policy called Urban Renewal. Through the use of several new state and federal postwar laws both with some ease the city was able to use eminent domain to tear down unfathomable amounts of Chicago’s early pre war housing stock, displacing thousands and destroying entire neighborhoods. Chicago hit its peak population of 3.6 million people in the late 1950s and anxieties of housing shortages, plus a growing suburban middle class exodus threatened to put the city’s tax base (which was then far more dependent on the residential neighborhoods) at risk.

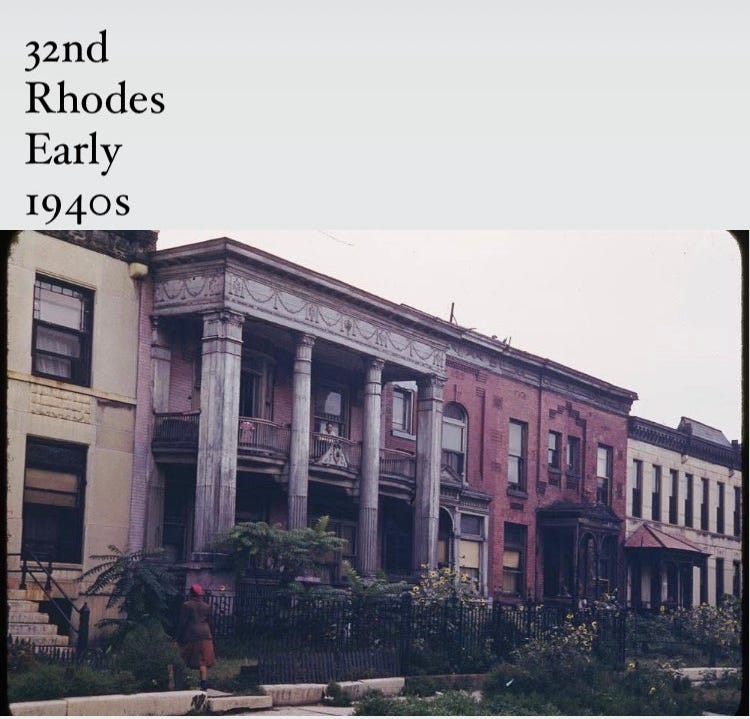

Real concerns on public health, coupled with well entrenched neighborhood racism fostered many of these ideas. Much of the remaining housing in neighborhoods in and around Bronzeville, North Kenwood, Oakland, Douglas, Woodlawn that we cherish today like the beautiful stone mansions of the 1880s up and down the boulevards were often converted to rooming houses to support a massive influx of migration post WWII. These buildings were woefully overcrowded and many did not even have indoor plumbing. Most of the residents of these buildings were black and many had recently arrived from other parts of the country.

32nd and Rhodes, Today

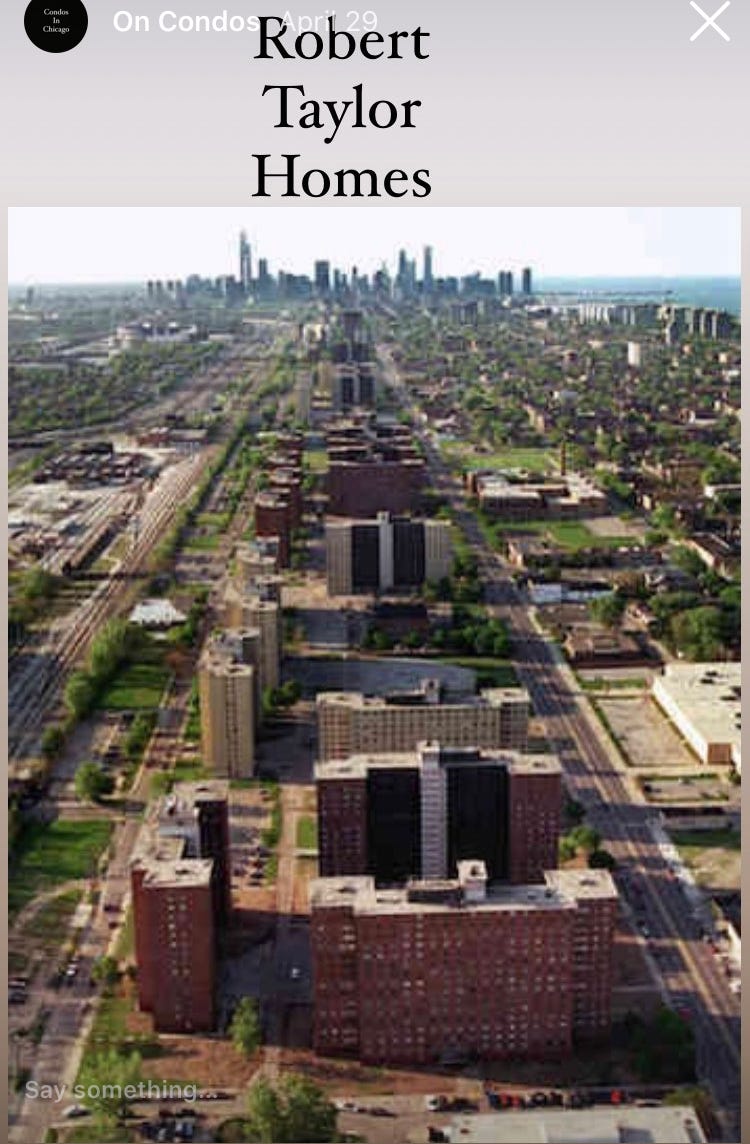

The Kennelly and then later the first Daley administration’s strategy towards modernization and potentially stemming the tide on suburban outmigration was to use the powers of the Chicago Land Clearance Commission to tear down enormous swaths of land and to build vertically. Community support for land clearing policies in parts of the city was often easy to find due to fears of the “black belt” expanding into surrounding middle class neighborhoods. Whole neighborhoods were destroyed and in their place came massive concrete towers with huge setbacks surrounded by open land: The infamous public housing complexes of Chicago.

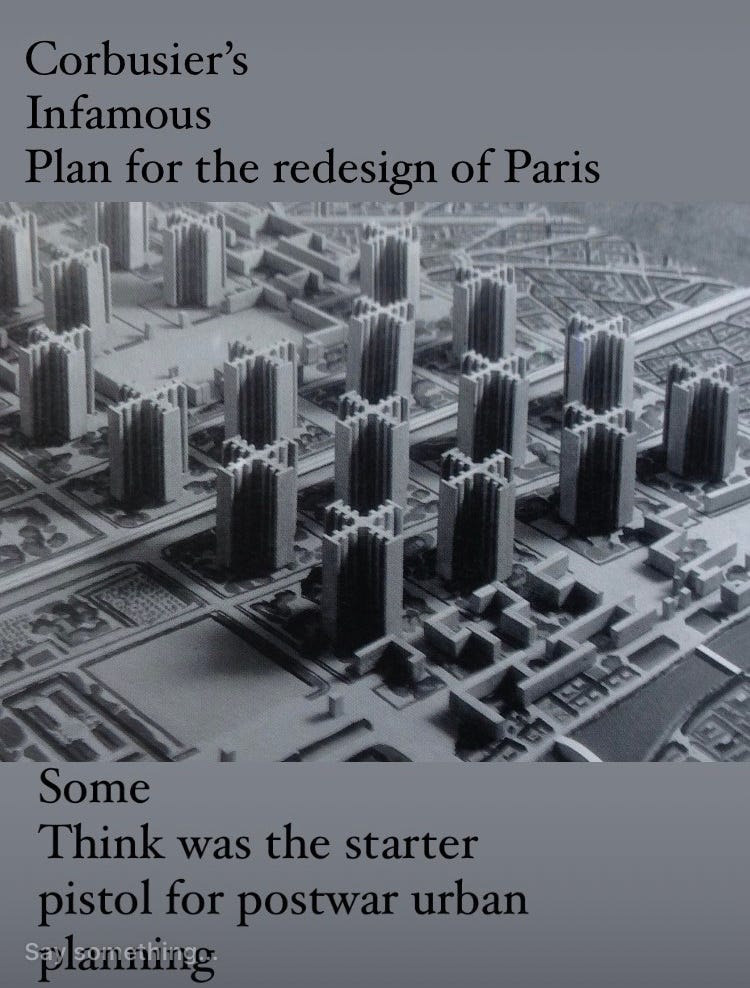

City planners for these areas rarely factored community input into their decisions for best land use protocols. Whether explicitly spoken of or not, urban planning concepts from Europe and the Soviet Union were often favored: Demolish low rise housing stock and replace with nondescript mid and high rise buildings set back on large land parcels.

Of course, many displaced residents were unable to move into these new buildings and those who did were packed into overcrowded, austere structures. The surrounding open land was always underutilized and often became hotbeds for the exploding crime rates of the 70s-90s.

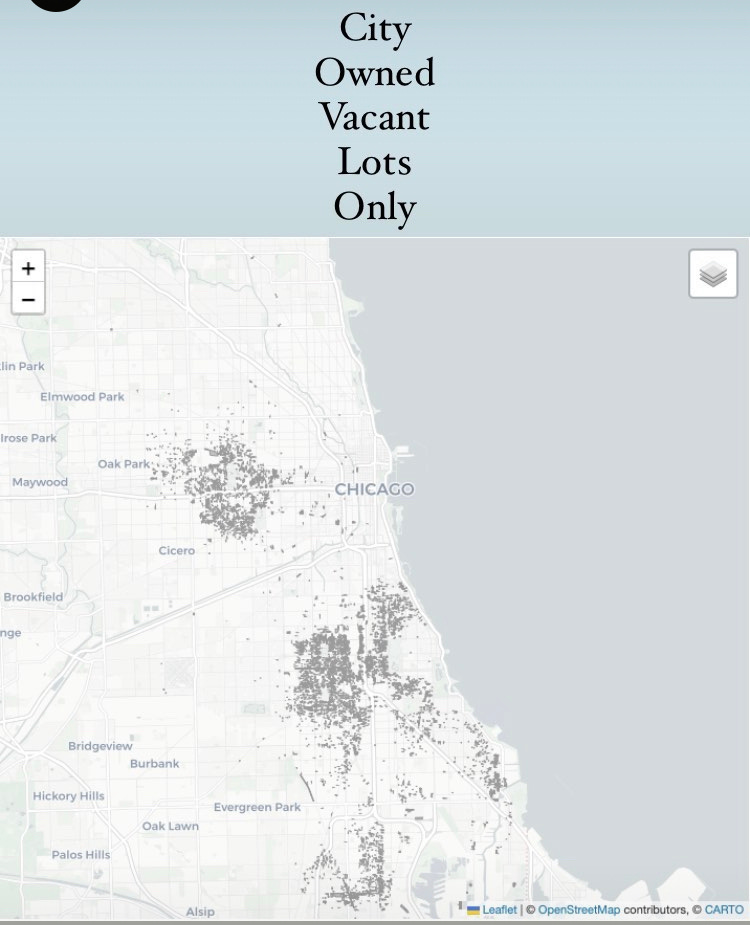

The population boom previous administrations predicted never came and these large scale public housing complexes were torn down leaving mass swaths of open land. By 2000, Chicago’s population had not grown to the 5 million residents that planners in the late 50s had predicted. In fact, the current population is 800,000 less than when these policies were enacted. Net population loss over the last 70 years greatly exacerbated disinvestment leading to more depopulation, more abandonment, and more teardowns

Today, we still have 30,000 vacant parcels of land in Chicago. 10,000 of these are city owned. How is this possible in a city with a world class economy and in a nation with a massive housing shortage and affordability crisis?

Infrastructure:

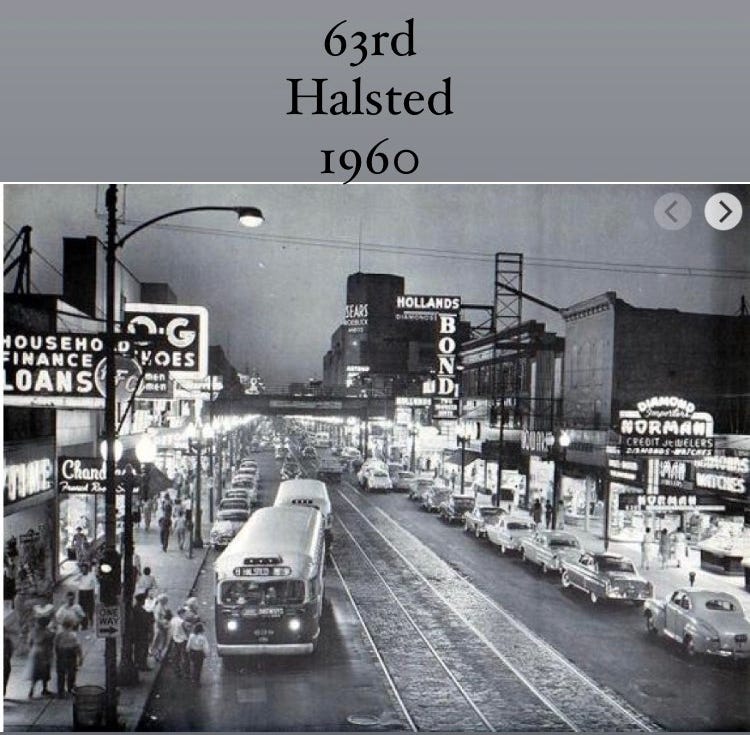

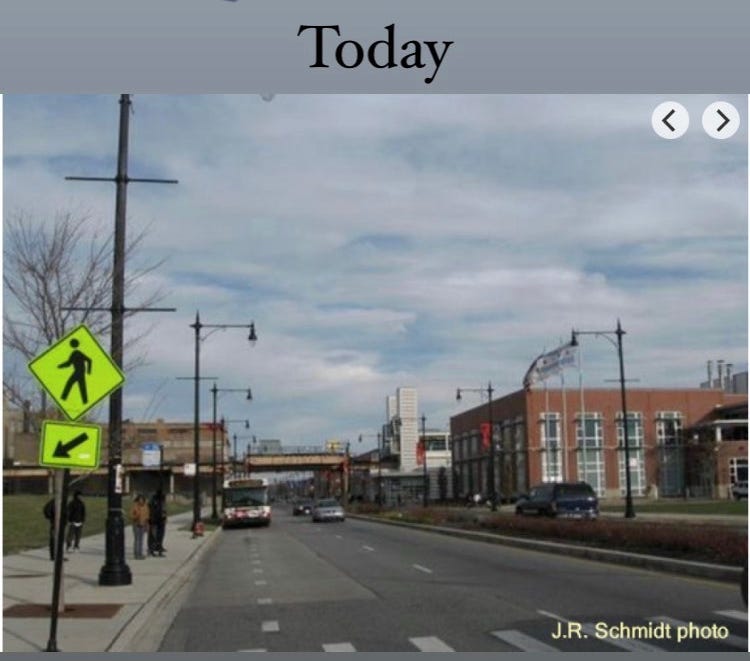

While many of the neighborhoods most affected by Urban Renewal land clearance are still rich with transit options, the walkability and livability indexes in these areas remain woefully low due to mass commercial tenant loss on their main corridors.

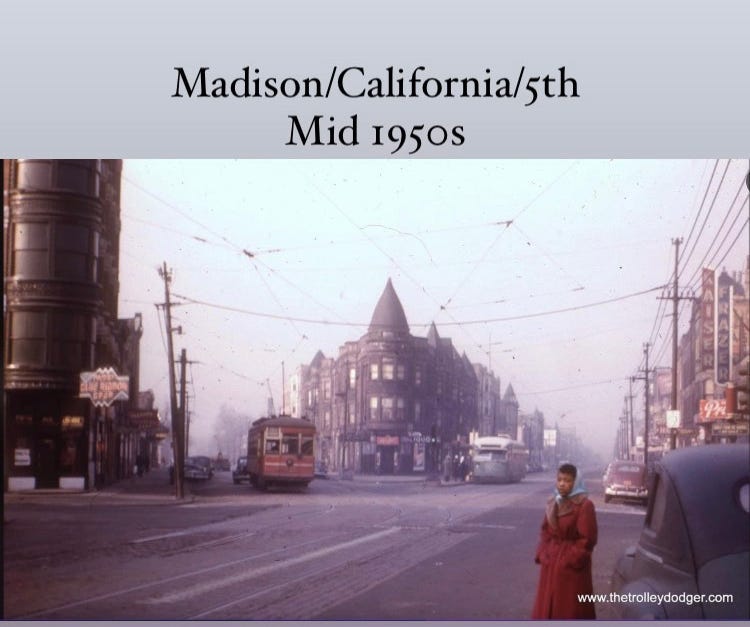

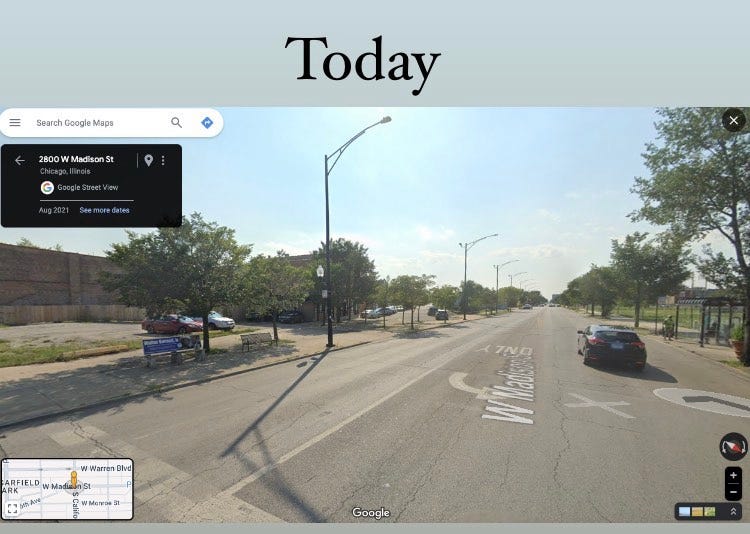

Once booming intersections and commercial corridors have been either long boarded up or reduced to rubble over the years. If not directly from Urban Renewal initiatives, depopulation lead to reduced customer base, which ultimately lead to vacancy, abandonment and then demolition.

5th and California/Madison

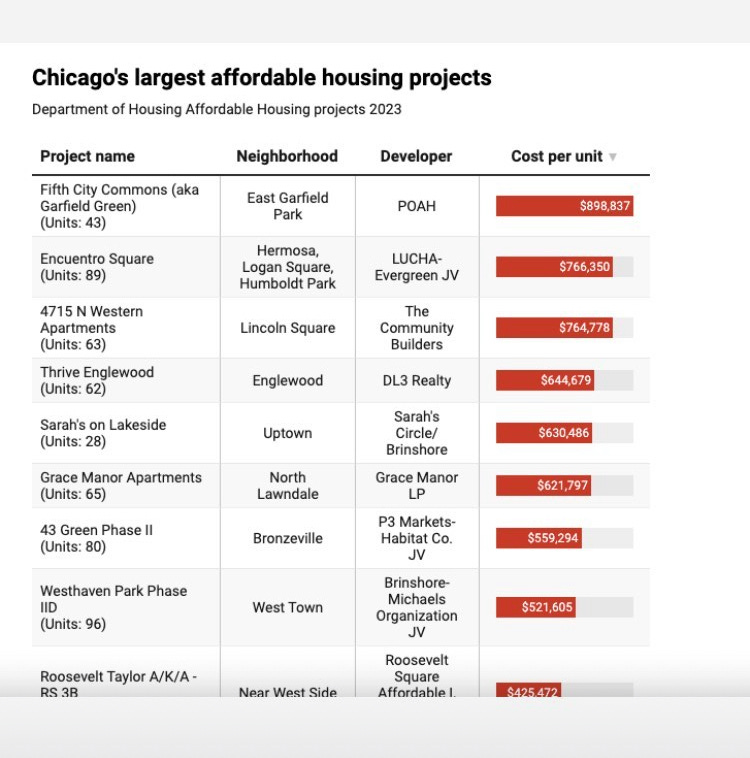

With an already reduced demand for brick and mortar retail and office space, getting financing to build mixed use or solely commercial buildings in low income, low density neighborhoods has proven next to impossible. Federal initiatives like Opportunity Zones have bore little fruit so far in Chicago and local programs to build affordable housing developments are coming in with shockingly high construction budgets. Major big ticket affordable housing projects in Chicago are far exceeding the market rate for similar size units, sometimes even exceeding the cost of ultra luxury units of the same square footage.

Construction Costs:

It’s no secret that construction costs both on labor and material have skyrocketed over the last four years. Overall cost of residential construction is 38% higher now than in February 2020. In addition, interest rates have more than doubled with many construction loan products topping 10% interest carry. While housing prices have gone up substantially as well, the margin between build and sale price has slimmed leaving builders with less profit.

When profit margin shrinks to these levels, far fewer developers are willing to take big risks on areas without a tried and true history of sales that will assure them that their target exit price is attainable. Lack of risk and unreliable demand in areas with high vacancy is one of the major reasons why you’re seeing seemingly nonsensical teardowns replaced with higher density condos in our wealthiest neighborhoods. Refer to the Webster/Seminary project in part 2 of this series for a good example.

Zoning:

One of the biggest ways developers have been looking to maximize profit amidst rising construction costs has been through adding density to projects. Higher density and unit count is a win-win for both the builder and the purchaser. Stacking the parcel with condos often yields a higher return for the builder and affords the buyer an opportunity to buy in an area where a single family home may be out of their budget.

The problem with this is Chicago’s most common zoning code, RS3 and its Lot Area Per Unit do not allow for the construction of anything other than a single family home. In areas where developers are taking a bigger risk, not being able to hedge by packing the lot with a higher unit count is a bridge too far. What’s worse is this zoning code post dates the majority of buildings in Chicago. Huge turn of the century or 1920s buildings are often non compliant with the 1957 zoning code foisted on them. This means if a building is in bad enough shape to require a teardown, a new building in its place could only be a single family home without a zoning variance.

Parking:

Almost every residential zoning code in Chicago requires a 1-1 parking ratio. This means for every housing unit built there is an off street parking space required. Even on lots with zoning more favorable to density, maximizing unit count is almost always impossible because of the parking requirements. On average, 28% of a city lot is dedicated to parking and yard space.

Appraisal Issues:

One of the most glaring issues preventing market rate for sale housing stock from being built in neighborhoods rife with inexpensive plentiful vacant lots is the prospect of the buyer being able to find financing.

With construction prices at an all time high, being the canary in the coal mine building or buying in a neighborhood without sufficient sales comps is going to have you wringing your hands praying for the unit to appraise at contract price. If the unit doesn’t appraise out at value the buyers are then forced to either change their loan to value ratio or put up more cash to close.

Some of these areas have never seen a condo development even in the early 2000s boom times. Appraisers are not infallible and banking on them sharing the vision the builder and buyer have for an area with no prior similar sales is just too big a risk for many.

Thanks for reading and happy new year!

One of the single best things I've ever read on Chicago housing. Question for you: if zoning liberalized across the vacant lots of the South and West sides, would those lots now become more viable residential construction opportunity sites? I assume there are some economies of scale that are applied here, but is there enough demand there to pencil out?