Does the South Loop Suck?

A neighborhood's transformation from an abandoned railyard and how one generation's planning ideals can hobble the next's property values

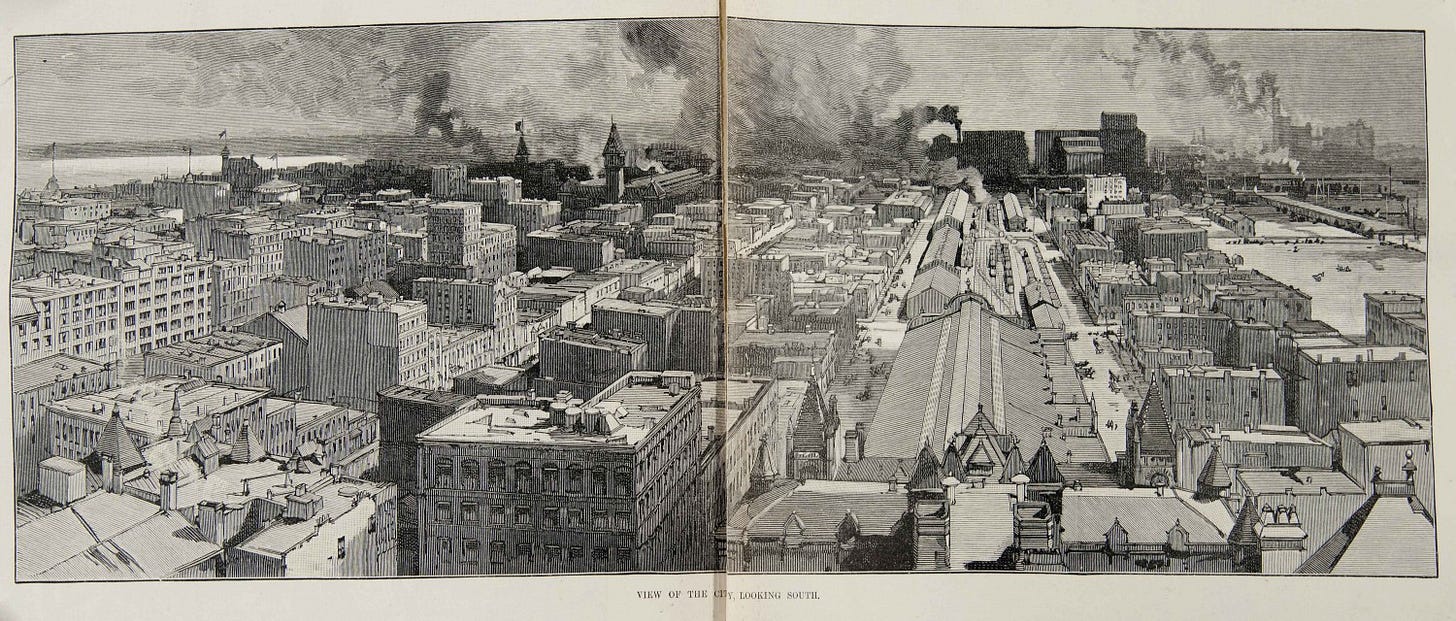

The South Loop, 1890s

Do you ever get the sense that some anonymous malevolent force is at play in Chicago? Some shapeless, formless entity that stymies the best-laid plans of our populace and continuously steers us into the morass?

In many ways, the South Loop is the physical embodiment of this phantom sabotage. The story behind transforming a 600-acre sea of disused railyards into a neighborhood is almost unbelievable by today’s standards. This new South Loop was borne out of the near herculean efforts of a few businessmen who, on top of their busy careers in other fields, dedicated 20 years of their time to an essentially civic-minded project. Their goal was above all else, to transform a post-industrial wasteland stretching from Polk Street to Cermak Road into a vital neighborhood that connected the optimistic post-war developments to the south to the bustling commercial Loop corridor. In many ways, they succeeded.

But to what end? When all was said and done, no profits were returned to the original investors of the 1600-some units built in the 51-acre ground-up first and second phases of the project. Although this original group of magnates accomplished their commendable goal of driving area-wide development after their original projects in Printers Row and Dearborn Park, the original fervor of South Loop development has since fizzled.

In my 13 years in real estate, the South Loop has almost always been at the bottom of my clients’ neighborhood list and while the reasons for this vary, they almost always fall under the same umbrella: the planning of the South Loop sucks. Why at the foot of the absolute city center are there acres upon acres of townhouse development that looks like it belongs in Mundelein? Where are all the businesses? Why am I seeing high-rise buildings left and right but nobody on the street walking around? Why despite the skyline towering over you does everything feel so far away?

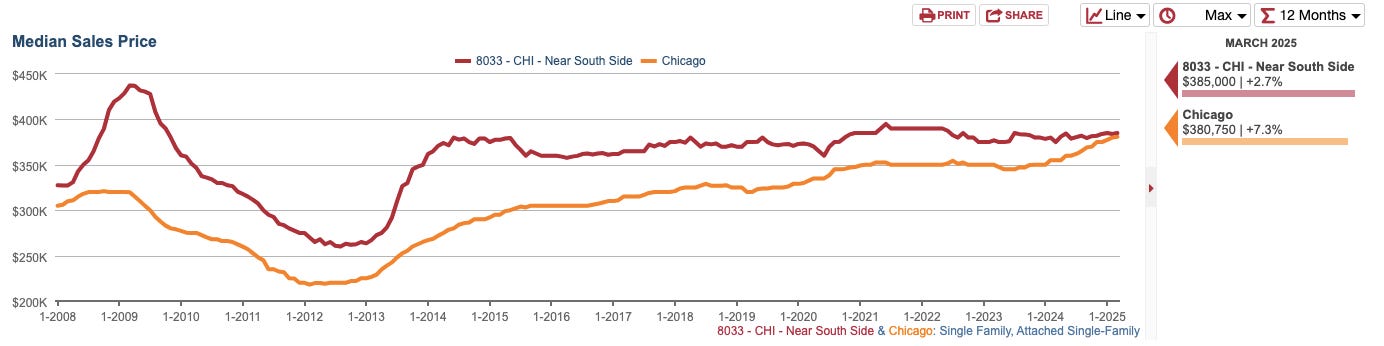

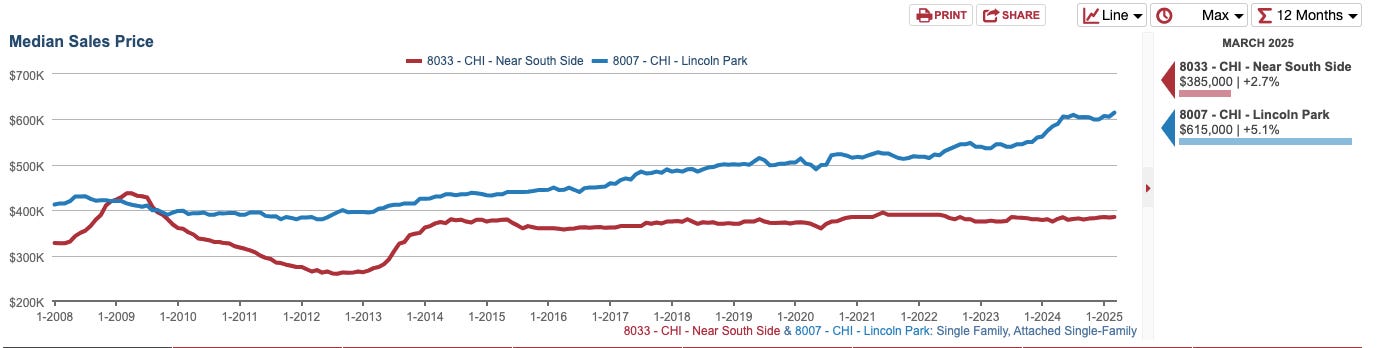

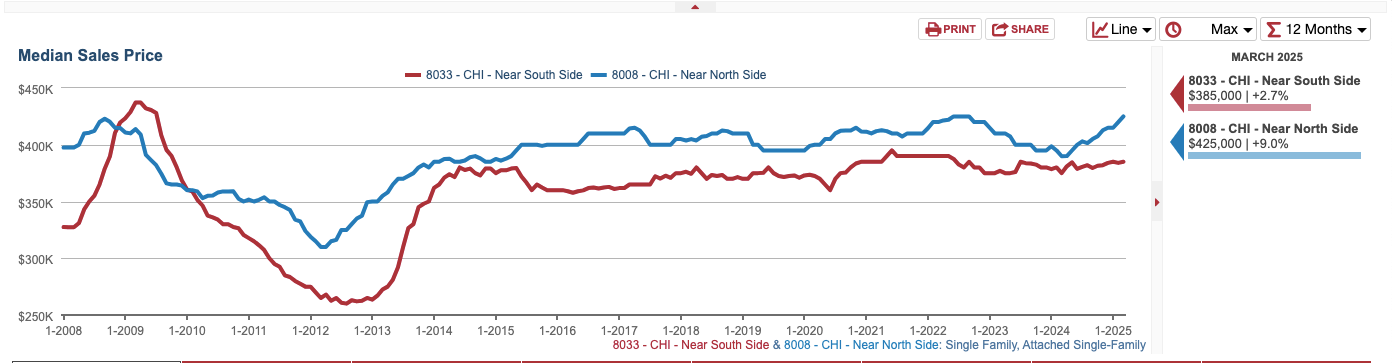

It’s not just anecdotal rhapsodizing from a few on the South Loop’s drawbacks, there is market data to support homebuyers’ preferences for other areas. The median sale price in the South Loop has barely budged in 10 years and still sits 12% under the Q1 2009 peak.

Median Sales Price, Near South Side 2008-2025

Median Market Time, Near South Side 2008-2025

Median Sales Price Attached Housing, South Loop vs City of Chicago

Not only has the market time per unit, a key indicator of buyer demand, exceeded the city baseline for the last 16 years, but the median condo price for the entire city is now within 1% of the South Loop’s median value. This is remarkable. The South Loop’s far newer housing stock has few of the operational problems of the older buildings in its counterpart neighborhoods north of Loop. The South Loop is also as centrally located as it gets and rich in transit options. Most importantly, it borders Chicago’s best amenity: Lake Michigan.

So what happens when one generation’s vision for optimized urban planning is wholly out of step with the next? Are housing trends seasonal and will low-density gated communities in the heart of the city become relevant again or did we squander the most important piece of undeveloped land in Chicago’s history?

The Context

Like most downtown adjacent neighborhoods of Chicago’s pre-fire days, the South Loop was once a collection of cobbled-together wooden shacks that then Mayor “Long John” Wentworth called the “dirtiest, vilest, most rickety, one-sided, leaning forward, propped up, tumbled-down, sinking fast, low roofed, miserable shanties.” He had a mind to clear the neighborhood but was more concerned with another area at the mouth of the river for which he reserved even more colorful language. Although it was spared by the great fire of 1871, another fire three years later leveled the shantytown.

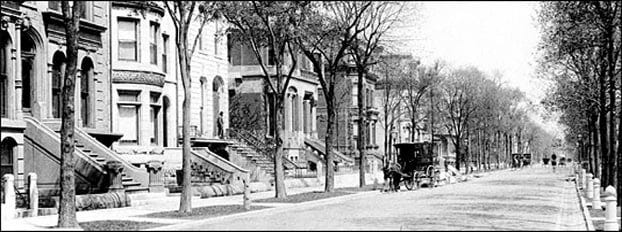

Tony Prarie Avenue c. 1890. Only a handful of these homes remain standing today.

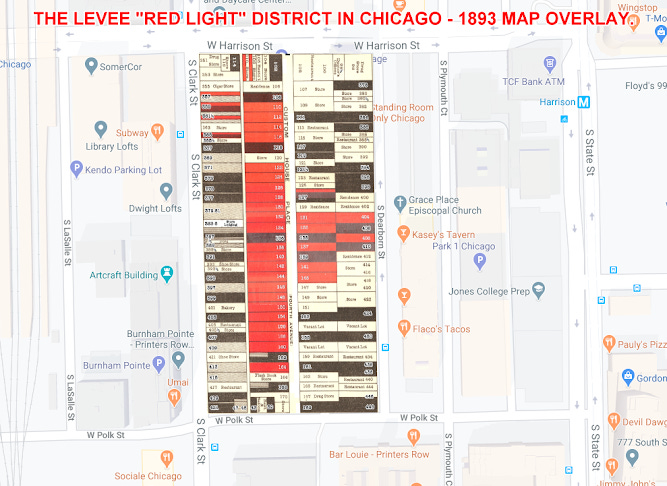

While Prairie Avenue, the area southeast of what is now the South Loop began to be filled in with the mansions of 19th-century captains of industry, the northwest section became home to much of Chicago’s ever-expanding railroad network. With transient commuters now being shuttled in and out of the neighborhood, brothels, gambling dens, and other houses of ill repute began to infill the area. As downtown Chicago began to grow southward, Mayor Carter Harrison undertook an initiative to move the red light district around Dearborn and Van Buren further south to consolidate vice in the infamous Levee District between 18th and 22nd Street from Clark to Wabash. More railroads and rail infrastructure filled the area in between.

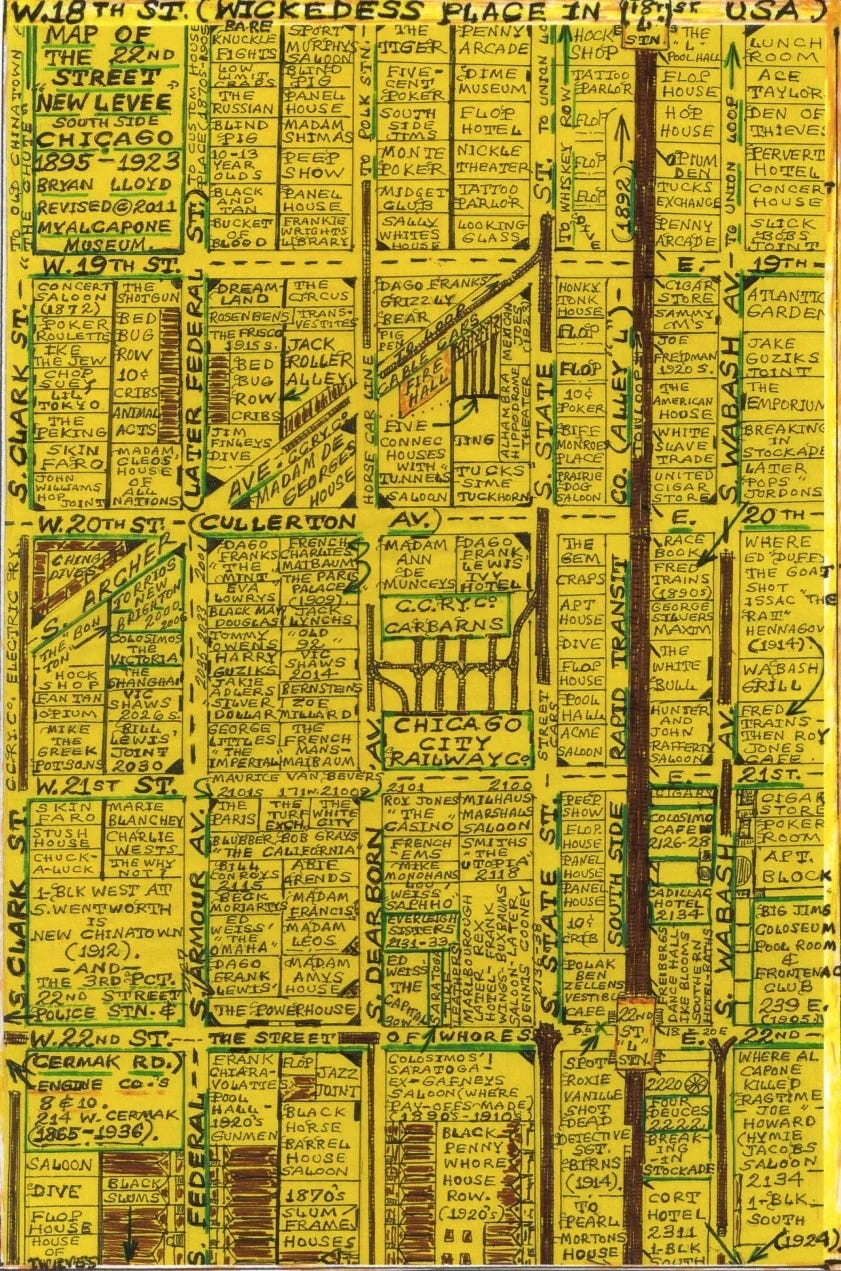

The original Levee Red Light District, overlaid on current map

The Latter Levee from 18th to 22nd Street, Clark to Wabash, each lot and its use noted

Nearly every inch of the Levee was filled with buildings dedicated to illicit activities enabled by Alderman “Hinky Dink” Kenna and “Bathouse” Coughlin. The phrase “slipping someone a Mickey Finn” originated here after a resident bartender and thief. The establishments ranged from the tony Everleigh Club, frequently patronized by the city’s elite to the down-and-out “Bed Bug Row.” The Levee was a constant bugaboo to the upper-class residents to the east. Prairie District occupants worried about vice encroachment to their neighborhood and the growing Christian Temperance Movement of the day wanted to shut down “the wickedest neighborhood in the country.” The government finally acquiesced to these pressures and the Levee was raided in 1911; the last brothel shut down in 1914.

The Everleigh Club in its prime (left) and right before its 1933 demolition (right)

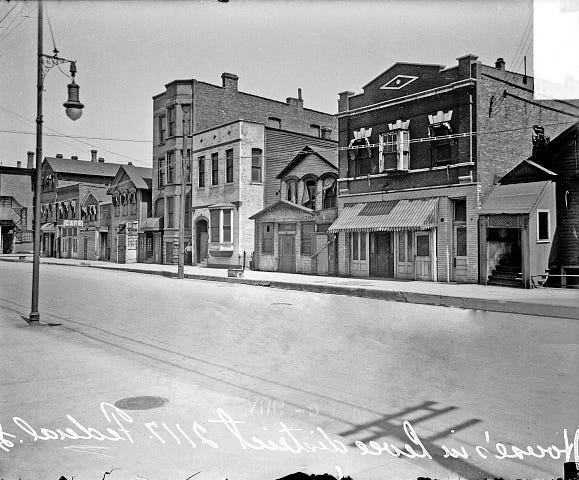

Federal Street, Levee District 1911

What was left of the Levee’s buildings was slowly torn down over the ensuing four decades through the city’s liberal use of the Urban Renewal land seizure policy. The remaining buildings between 18th and Cermak which had devolved into “a shabby mix of junkyards and rundown bars” were finally seized, torn down and the southern tip transformed into the Bertrand Goldberg-designed Hilliard Homes in the mid-1960s. The once grand Prairie Avenue mansions to the east began to be converted into rooming houses or were torn down altogether. Save for a few seedy hotels and businesses in the eastern section of the South Loop, west of State Sreet was almost nothing but railyards, train depots, and vacant land.

The Hilliard Homes stand where the southern tip of the Levee District once did

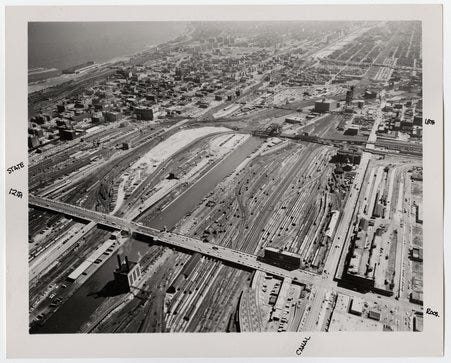

As the 20th century progressed, the need for Chicago’s mighty train infrastructure dwindled. Freight began to be moved cross-country in trucks, and the extensive highway system saw more and more Americans traveling by car. Except for a few commuter lines to the South Suburbs, most of the railyards south of downtown were gradually shuttered and abandoned.

The railyard graveyard of the South Loop, 1970s

Disused or not, Chicago couldn’t use its Urban Renewal land seizure and clearance policies to grab this railroad-owned land as it had in so many other areas. Mayor Daley had tried to put his pet UIC project here but untangling and negotiating with the 13 individual owners of the railyard land proved even more of a struggle than seizing land and building the college in the bustling Little Italy to the west.

It wasn’t until big-ticket, big-publicity projects like the Sears Tower brought corporate validity to the southern end of the Loop in the early 1970s that a few movers and shakers in Chicago’s business community began to wonder what was going on with this 600-acre abyss and why nobody was doing anything with it.

The Players

Even in the early 1970s, there was growing concern that the Loop had become nothing more than an 8-5 pm, five-day-a-week commercial corridor catered to a new commuter class. Part of Mayor Daley’s plan to make up for the tax revenue lost from growing numbers of these suburban white-flighters was to fortify the city’s downtown. Let’s shift the development and tax focus from the neighborhood homeowners to the commercial interests downtown a bit. After all, these newly minted suburban denizens were still coming downtown each day to work. The result was to undermine what little small-scale mixed-use and manufacturing was left in the Loop during the 1960s and allow easy access for builders to erect the huge hulking glass towers that make up the city’s skyline today.

The problem was, what was everyone doing when the workday was over? Rushing to grab the 5:31 home presumably. This left large canyons of inactivity on nights and weekends in the Loop. The emptiness would perhaps attract “undesirables” who still made the city their home coming downtown after hours. This along with the growing outmigration from the city in the 1970s turning from a trickle to a river left some executives who relied on the Loop’s desirability to their middle-class white workforce uneasy. Perhaps if there was a community where these white expats would actually want to live adjacent to the Loop, that could stem the tide of outmigration.

Out of all the hands on deck to will the South Loop into existence, none were more integral than Tom Ayers, Ferd Kramer, and Phil Klutznick.

Tom Ayers

Tom Ayers was CEO and chairman of ComED, he had no experience in real estate development. He sat on the board or chaired seemingly every white shoe WASP organization in Chicago. Funnily enough, his son is the famous left-wing activist of Weather Underground fame Bill Ayers. He became chairman of the Dearborn Park Committee.

Ferd Kramer

Ferd Kramer was the namesake of Draper and Kramer and one of the biggest players in real estate development and mortgage lending nationwide at the time. He made his reputation on the imposing Lake Meadows and Prairie Shores developments (in my opinion some of the worst displays of mid-century planning and policy) to the south. He was tremendously driven and without his chutzpah, it is doubtful the New South Loop would have ever gotten off the ground. Kramer had grown up on Prarie Avenue just as it was losing its prestige. He was determined to bring the area back to life.

Klutznick, during his time as Secretary of Commerce

Phil Klutznick is most well known for his tenure as the Carter Administration’s Commerce Secretary and as a soothsayer to the Israeli Knesset. Before this, he developed the first copy/paste post-war suburb in the US, Park Forest, and went on to build a slew of suburban shopping malls in collaboration with Marshall Field’s in the 1960s and 70s.

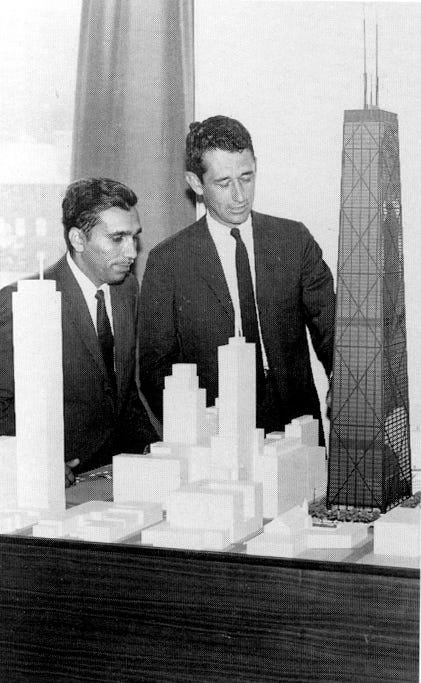

Graham, in front of a Hancock Center model

Bruce Graham, the favorite son of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (“SOM”) was the lead architect and planner on the project. Graham designed both the Hancock Center and the Sears Tower. He was the design face of and came from the SOM mid-century edict of glassy post-Miesian skyscrapers in every city, worldwide.

The Plan

From the get-go, the Dearborn Park committee as they came to be known, knew this undertaking would be neither easy nor profitable. Syndication agreements looked like scared-straight cautionary tales rather than incitements to invest. Still, local banks, Fortune 500 companies, and even the Archdiocese lined up to fund this private development with a heart of gold.

The railyards looking south from Dearborn Station

It took years of haggling with the different railroad companies and receivers just to purchase the first parcels. 51 acres from State-Clark-Polk-15th Street. Getting the infrastructure improvements proved even more challenging. In a handshake agreement (as was his custom), Mayor Daley agreed to spend millions of dollars to fund the new project’s water, sewer, and street systems. The problem is he died in 1978 and convincing his replacements to fund 7 million dollars of infrastructure work without a written agreement in place was a nightmare. It wasn’t until right before the first occupants, (and 3 mayors later) moved in that the sewer and plumbing work was done. The new residents lived without paving their whole first winter.

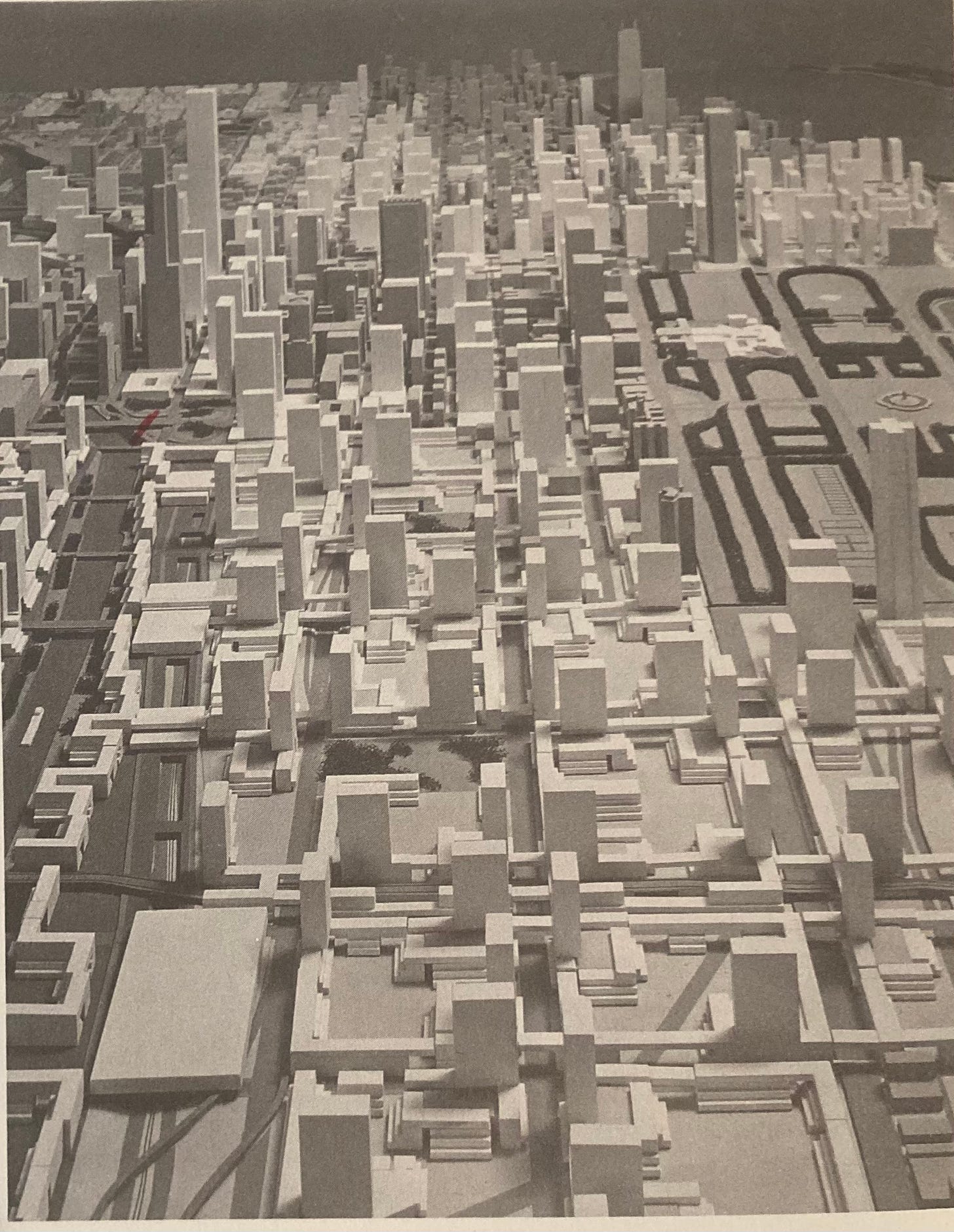

SOM’s initial plan for the old railyards was enormously ambitious. Ten hyper-dense square blocks with between 2,000 and 3,000 units apiece; 25,000 units on the 250 acres extending west to the river. 8-story mixed-use bases tapered to terrace townhomes and then to high rises. The structures were massive with some buildings in the plan being 700 feet long. A light rail would be built to traverse the new neighborhood. Later that year SOM would go public with this grand vision, dubbed the Chicago 21 plan.

Skidmore, Owings, Merrill Megablock plan for the South Loop, Chicago 21 Plan

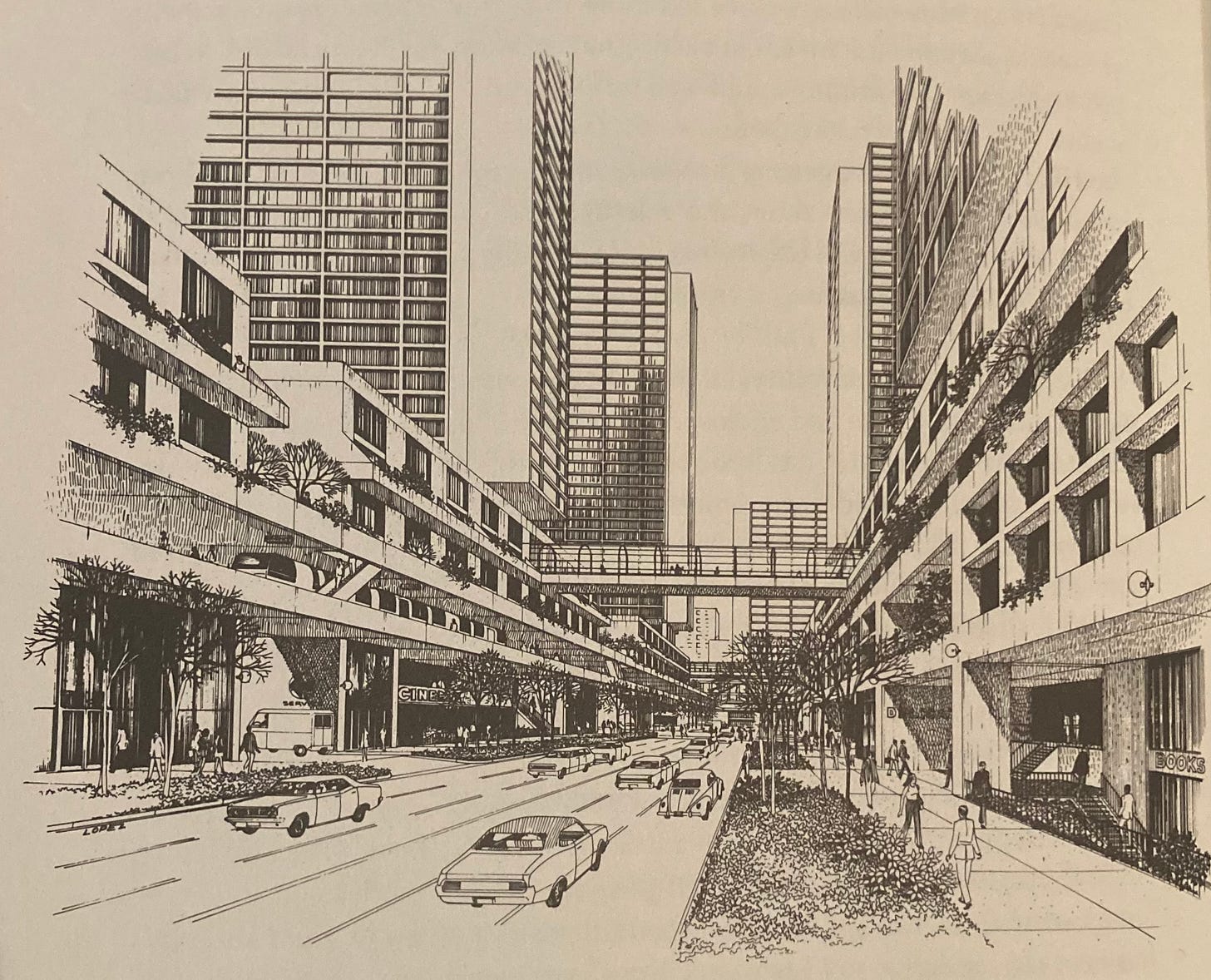

Street detail from Chicago 21 Plan. Note the monorail, brutalist multi-story retail, and glass catwalks.

Around the same time, Bertrand Goldberg, fresh off his big successes with Marina City and Prentiss Hospital was actively looking for a development partner for his plan for the area. He was well acquainted with the wasteland between his Hilliard Homes project and the southern tip of the loop. He had an equally ambitious idea to SOM: triads of 70-story towers with 1,000 apartments each, packed tight into the eastern section of the neighborhood. Goldberg’s version was even more dense than SOMs with 15,000 units on the first 30 acres alone. It would then expand outward. When SOM got beautiful glossy Bodoni and Helvetica books made to tout their new project around town, Goldberg narrated a film laying out his vision which he famously showed to potential investors. Goldberg, perhaps by nature of his idiosyncracies and lack of connections to the Chicago Elite was never a serious contender in the eyes of the stodgy Dearborn Park Committee. SOM got the project. Goldberg eventually got his River City, albeit pared down.

River City hyper dense triad complexes to be west of the river. Buildings would feature shops, library, post office, health center, and daycare on the 54th floor of each building. Unbuilt.

There is one thing both of these legendary architects concluded. That a neighborhood directly abutting the central business core of Chicago should be vertical, dense and vibrant. Like the neighborhoods north of the Loop, buildings should be mixed-use, with businesses and housing integrated in the same development.

The top brass at the Dearborn Park committee disagreed. These men were well into their 70s at first groundbreaking and the brutalist embrace of SOM and Bertrand Goldberg’s hyper-dense plan laid outside their comprehensions of liveability.

Park Forest, IL: the original postwar suburb where Phil Klutznick made his bones.

Tom Ayers, a long-time Glen Ellyn resident, didn’t think families would want to live in hyperdense superblocks in terraced houses or otherwise. Klutznick, who cut his teeth on large-scale development in the suburbs, thought the design was austere and Soviet. Ayers said it best “We were looking for a Model T, not a year 2000 future car.” To the chagrin of Bruce Graham, the Chicago 21 plan died on the vine.

Townhouses of Dearborn Park

What was the Model T of the late 1970s Chicago? The townhouse. With Chicago’s white-collar, middle-class residents still fleeing for greener suburban pastures, townhouses, the committee decided, would bring them back to the city. The scale of the plan was drawn back considerably to a measly 1600 units. The mixed-use portion of the original plan was scrapped as well. A suburban cul de sac didn’t have stores. Besides, the density in the neighborhood at the time was insufficient to attract a large tenant like a grocery store, and worry of a loitering “element” nixed any chance of small ground-level storefronts on seedy State Street connecting to the residential component. Despite the city requiring 50,000 SF of retail in phase 2 of the development, the committee balked and got the city to reconsider.

The first Dearborn Park townhouses were delivered in 1979. Despite record-high interest rates setting in right after the first phase of the project was completed, the units sold well.

To the surprise of the Dearborn Park Committee, very few were the families that they predicted ended up occupying the development. Only 40% of buyers were married couples and less than 8% had kids. Most of that 8% did not have school-age children. Only 12% of buyers were moving from the suburbs and they were primarily empty nesters. 20 years after the Dearborn Park Committee hatched its first plan for the land, the last units were sold.

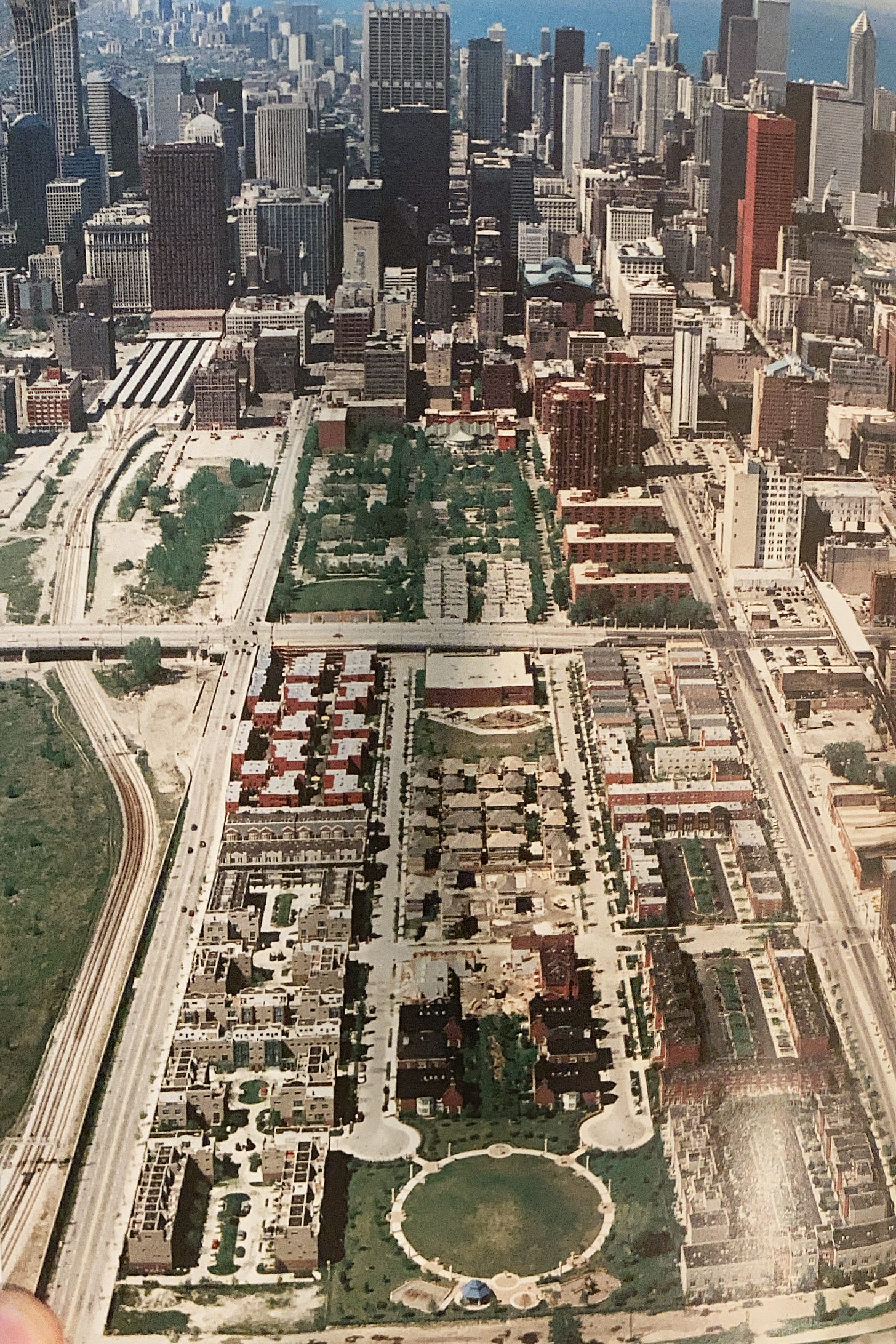

Even though returns on capital were scant, the civic-minded push behind this initial development succeeded. The South Loop filled out in the coming decades. The hulking industrial north became Printers Row. New glassy towers off Michigan and Roosevelt Avenues filled in the last remaining railyard along the lakefront, along with more townhouses. Everywhere.

Dearborn Park, 1990s

Does the South Loop Suck?

The post-2008 hangover from the booming growth of the 90s and 2000s hit the South Loop hard. The median sale price fell 41% from 2009 to 2012. The market bounced in 2013, but prices have since stagnated with no upward value momentum in 10 years. By nearly every metric of market health, the South Loop underperforms against the City of Chicago as a whole. Why?

While there is not one answer to this, my theory is that price stagnation in the South Loop ultimately boils down to the expectations of urban buyers today versus the existing built environment in the SL.

I conducted an informal survey online about the South Loop last week and got about 50 responses. They were almost overwhelmingly negative. Most of the feedback was pretty in line with what I’ve been hearing from residential clients over the years:

“Despite the appearance of density, it isn’t very walkable”

The idea of walkability has evolved over the years in Chicago. In urban, pre-automobile America, being able to walk to business for basic subsistence was a necessity. By the mid-21st century, cars had moved from a luxury to a household essential, and these dense, “inner city” mixed-use neighborhoods became seen as crowded and substandard options for middle-class life.

After decades of car-oriented urban planning upending the original low and mid-rise streetscapes of Chicago, the populace, planners, and builders in the last 20 years have become more cognizant of the importance of the pedestrian experience in the city. New Urbanism has become the phrase ubiquitous with low-rise but still dense, mixed-use districts where commercial development mixes in or lightly tapers off into 2-4 story residential buildings on side streets. Really, how cities have been built for centuries. Walkability in these areas is defined by both living and commerce integrated on the pedestrian level. It is in neighborhoods like these where Chicago’s housing market currently performs strongest.

Lincoln Park Attached Single Family Median Sales Price 2008-2025

Lincoln Park is the perfect example of the gradient effect of New Urbanism. Despite vast differences in pedestrian experience in each neighborhood, the South Loop and Lincoln Park have about the same population density of c. 20,000 per mile. Densest by the lake, Lincoln Park tapers off into primarily singly family home districts in its western sections. Whether in hyper-dense Clark/Fullerton or single-family heavy Diversey/Ashland, no part of Lincoln Park is ever outside a few blocks walk to basic neighborhood commercial amenities.

Distance to place of work, a main attraction the Dearborn Park project touted in their property marketing material no longer seems to be a relevant metric to property value either. Both of these neighborhoods share the most common commuting destination for residents in the Loop. Still, even though the South Loop is mere blocks from the Loop and Lincoln Park is several miles north of it, the median sale price in Lincoln Park has exceeded the South Loop every year for the last 15 years. This margin between median sales price continues to widen. The median sale price for an attached housing unit in Lincoln Park is now 48% higher than in South Loop.

“There is a lack of small and destination businesses”

Neighborhoods rich with small businesses located on pedestrian-friendly corridors have been shown to have a huge correlation to property values. A 2011 study conducted by Civic Economics showed that neighborhoods with a high number of independent businesses saw home values outperform citywide markets by 50 percent over a 14-year span.

When the South Loop was first developed in the 1970s and 1980s, attitudes toward small urban businesses were much different than today. The cute gentrified shoppy shop was yet to exist and a prevailing sentiment toward small-scale mixed-use in the mid-1970s was that it attracted ne’er do wells and loiterers.

The “Suburb in the City” model wanted none of this. Instead of the more prevalent mixed-use corridors with commercial at ground level with residential above, first-generation Dearborn Park buildings on State Street were intentionally designed to have brick walls facing street level to give the residences a more insulated feeling.

The result was one business in the entire 10-block by 4-block Dearborn Park section and two businesses in another 10-block by 4-block section of the East of Michigan-Lake-Roosevelt-Cermak Central Station (1990s-2000s) section. Businesses are relegated almost totally to two streets, Michigan Avenue and Wabash in the whole neighborhood. This is remarkable for an area being at the foot of the Loop.

Dearborn Park, South Loop 10x4 blocks with zero businesses

Central Station south to 21st St. Two businesses in a 10x4 block radius

Let’s compare this to a similar section in a neighborhood equidistant from the loop to the north. From Chicago Ave (800 N) to North Ave (1600 N) between the same State and Clark Streets, there are dozens of businesses. Restaurants, grocery stores, and small shops all mix in with residential.

Gold Coast, Chicago-North Ave, State to Clark

Although it’s had its own problems with property values of late, the Near North Side, the South Loop’s northside counterpart to the Loop still handily outperforms the South Loop in median value. After having a lower median sales price in attached housing in 2009 than the SL, the Near North Side was hit less hard after the 2008 correction and has since bounced back to pre-recession levels. Even considering an older housing stock, the Covid exodus from downtown, and the 2010s preference for “New Urbanism” style neighborhoods, the Near North Side has continued to see growth.

Near North Side vs Near South Side, median sale price 2008-2025

“There’s an eerie, suburban quality to the neighborhood and housing stock that’s amplified by how close it is to the Loop”

This is the most common of the South Loop gripes that I hear.

The South Loop was built this way by design. The pantomime of 70s and 80s suburban development was meant to be a finger-in-the-dike of the mass outmigration of white and middle-class city dwellers and their families. There was one problem though - no matter what the development looked like, this target demographic just didn’t want to live here.

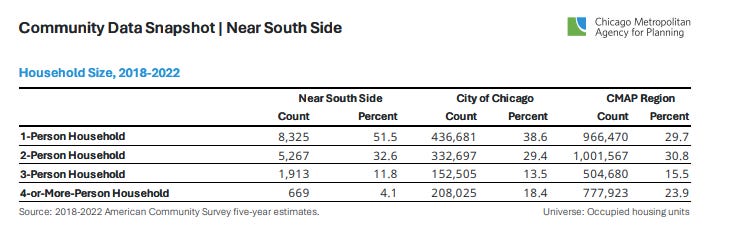

Only 40% of buyers in the first development phase were married couples and less than 8% had children. Only 12% of these buyers came from the suburbs. When the entire western section was built out, less than 25% of the occupants had children. Most of the children were not school-age. The discrepancy has only widened since. As of 2022, 83% of the population in the Near South Side is 1 and 2-person households.

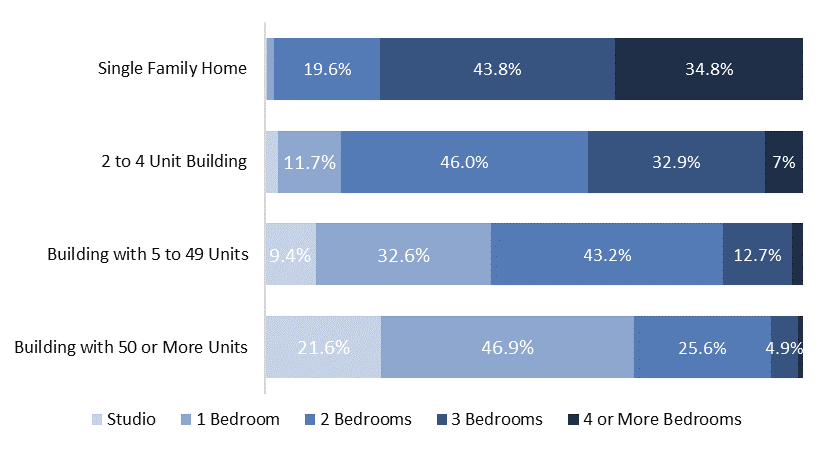

31.5% of the population of the South Loop is between 20 and 34. The prime age for urbane, child-free city living, a demographic that neighborhoods with such central proximity to the Loop have wholeheartedly embraced for years. New construction in Loop-adjacent neighborhoods has almost exclusively been large-scale 50 + unit rental housing where the unit breakdown is more skewed toward smaller 1 and 2-bed units than larger units geared toward family living.

Breakdown of unit size in various types of multi-family rental housing, IHS

The irony is, middle and upper-middle-class families did eventually come back to the city. In droves. Just not where the builders and planners of the South Loop ever considered. North Center, Uptown Logan Square, Wicker Park, and West Town were all totally looked over as viable options for suburban housing alternatives and dismissed as ethnic ghettos by the powers that were in the 1970s.

In just the last 10 years, single-family homes have doubled in price in Logan Square, grown 44% in West Town, and jumped 40% in North Center. Median income is way up, residents with four-year college degrees are way up, while unit count per lot is way down.

City families, as it turns out, want to live not dissimilarly to their urban forebears. They want single-family or large condo homes on a low-rise block gradually tapering up in density as the commercial corridor approaches. They don’t want a random planned development dropped in the middle of a hulking commercial abyss with nothing to do.

What If?

However you feel about the South Loop, it ain’t changing anytime soon. Buying out multi-PIN housing under different HOAs and redeveloping the land would be as herculean of a lift as turning an abandoned railyard into a city neighborhood.

If the stars had all aligned and SOM’s imposing superblocks or Bertrand Goldberg’s triad towers had been built in the South Loop, would the attitude toward the neighborhood be any different today? Would it be a coveted, brutalist icon of the city or another relic from the Soviet-esque mid-century tower messes that dot our landscape?

Maybe eventually return-to-office actually happens and inspires a whole new generation of buyers in the South Loop who live in the development as it was originally intended, with their families, enjoying an easy commute. This time at a bargain.

Great post, and answers a long standing question I've had about why that area feels so desolate despite having newer seeming housing. Q for you: when you were determining how many businesses were in a 10x4 block, were you working off a particular dataset?